What is WCAG and Why Does it Matter

Why should we talk about Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)? The present and future of engagement are online and web based. With the growth of the metaverse, ongoing drive towards digital transformation and meteoric rise in online purchases, the ability to deliver a great digital experience has become table stakes.

Trend trackers have pointed out how much more important the web experience has become since the start of the pandemic. But for the more than 1 in 5 people with a disability, these experiences might come with caveats. Worldwide, more than 220 million people have a vision impairment of some sort and over 2 billion have a disability of some kind. What implications does this have for web design? Quite a lot!

History of WCAG

The need for a set of web content accessibility guidelines was recognized decades ago. We’ll explore what those standards are, but how have they evolved over time, and when did they first come together?

To find the origins of WCAG we have to go back to before the Y2K crisis. Back to the previous millennium. The year 1999. On May 5th of that year, the HTML-focused WCAG 1.0 helped shaped the standards for web accessibility and digital experience. In 2008, those rules got an update in the form of WCAG 2.0.

Where the original had focused on HTML, the new guidelines (and the 2018 WCAG 2.1) expressed a technology-agnostic approach to accessibility for “web content on desktops, laptops, tablets, and mobile devices.” The goal of WCAG overall has not changed from creating a more accessible web environment, but each update has given additional guidance on this critical topic.

What Does WCAG Require?

The standards set out in WCAG 2.1 cover four key factors for accessible design along with a series of conformance criteria to evaluate WCAG compliance. In particular, WCAG 2.1 indicates web content should be perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust. What do these mean?

1 Perceivable

“Information and user interface components must be presentable to users in ways they can perceive.”

If a user cannot see, hear, or otherwise interact with web content, it is not accessible to them. This means, for example, that non-text content should have transcripts, alt-text, or other features meant to enable screen reading. Perceivable design isn’t limited to text accessibility, but WCAG 2.1 has additional guidelines on creating more perceivable content.

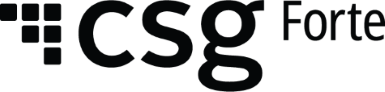

Example: Thanks to labels for all text fields in the screens of CSG Forte Checkout, users can understand what information each field is meant to include, allowing them to complete the form.

2 Operable

“User interface components and navigation must be operable.”

If a user cannot interact with the interface or navigation as designed, then the content therein is not accessible to them. One way to address this is to ensure that all interfaces have keyboard-based alternatives to mouse-based operation. Other types of operability blocks exist, but WCAG 2.1 provides several ways to ensure operable accessibility.

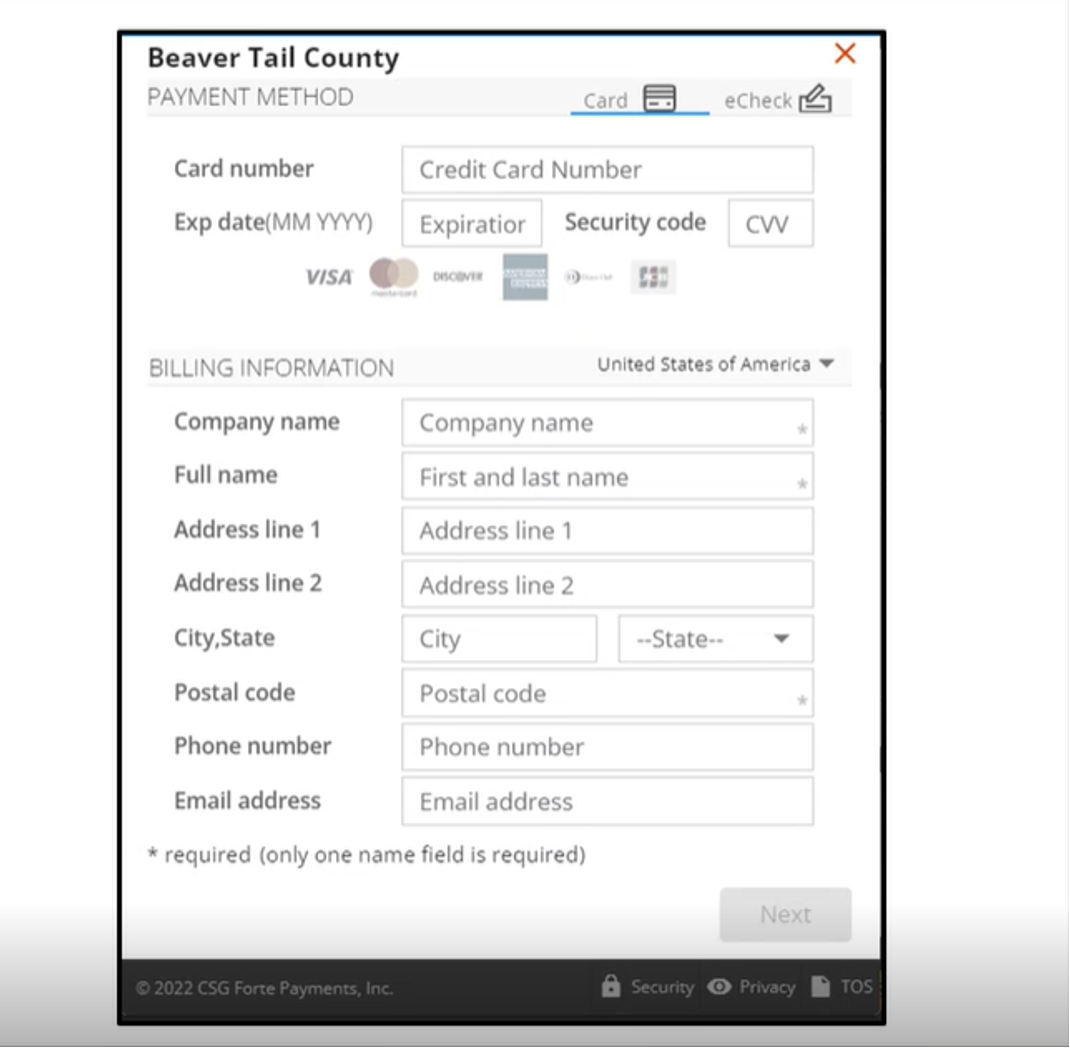

Example: Thanks to correct contrast ratios and keyboard controls to the date picker tool in various CSG Forte offerings, users can input the date they want to pay their bill using only the keyboard.

3 Understandable

“Information and the operation of user interface must be understandable.”

If a user cannot understand the content or user interface, then it is not accessible to them. The most basic understandability feature is including language options and translation-friendly pages, but clear labeling and acronym explaining features are other techniques to make web content more understandable. Whatever web content you create, you want your readers and users to understand it. Following the WCAG guidelines makes this that much easier.

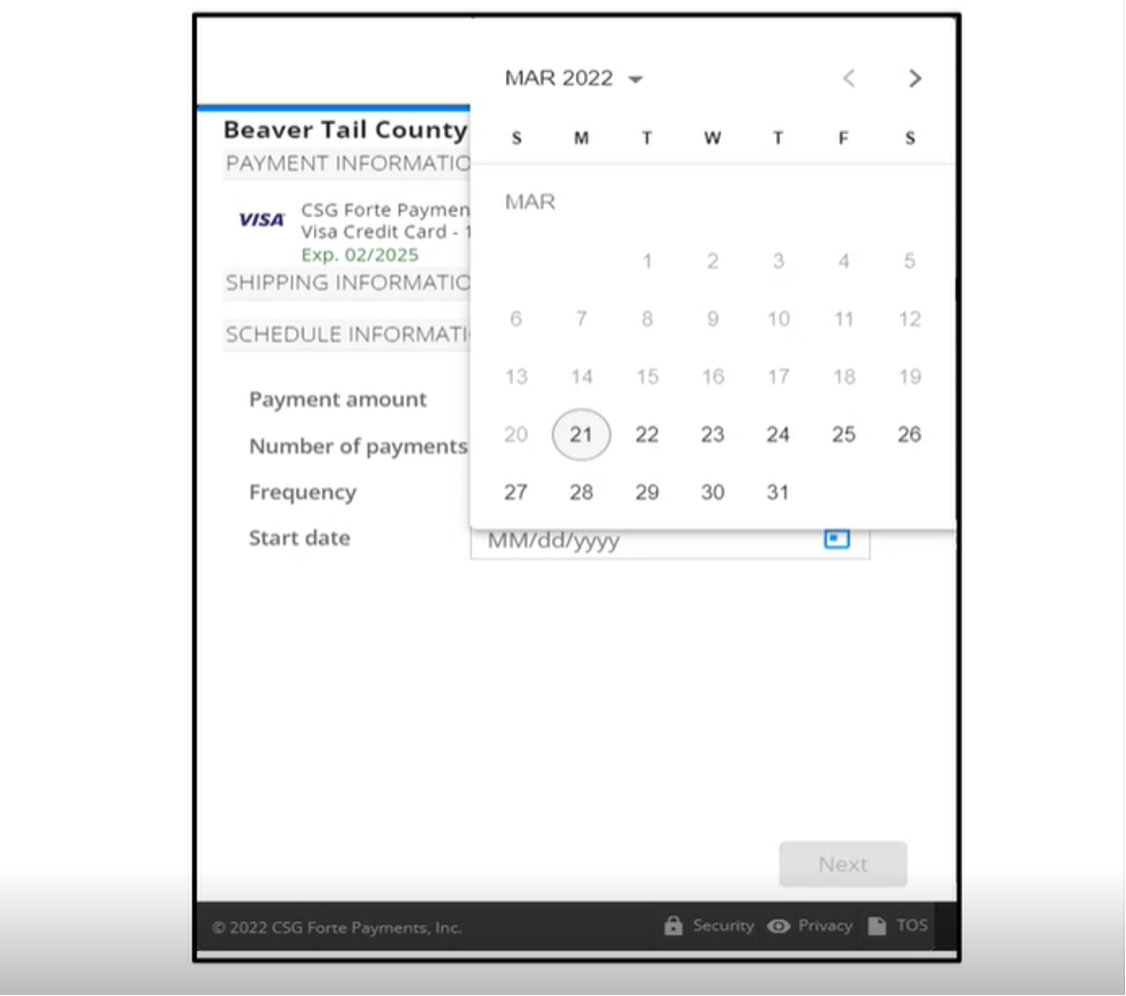

Example: Because CSG Forte error messages are described in text along with outlining for invalid input fields, users can parse error messages they might not otherwise understand.

4 Robust

“Content must be robust enough that it can be interpreted by a wide variety of user agents, including assistive technologies.

Where the other three factors are focused on making web content accessible to the user, the “robust” category of WCAG guidelines is focused on making content available to technologies used by those users. This means ensuring that pages are parse-friendly for text-to-speech and other technologies.

Accessibility Regulations

Where WCAG is a set of guidelines to create more accessible content online, there are other considerations for web content as well. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and Section 508 (508) contain standards for web accessibility. Unlike WCAG, ADA and 508 have legal ramifications.

Section 508

This regulation is meant to ensure that the federal government provides accessible services over all information technology communications channels. This extends from phone to web and beyond. Where WCAG provides wide reaching guidance on accessibility, 508 has specific requirements for federal offices and services. These include providing accessible computer, phone, and mobile services to employees and citizens.

Americans With Disabilities Act

ADA regulation is meant to prevent discrimination against Americans with disabilities by businesses, non-profits, and governments. While ADA regulations apply across more areas than web content, digital experiences should be made accessible as well. Although ADA has existed for over 30 years, many websites and digital products have no yet achieved ADA compliance.

OTHER READING: Did You Know CSG Forte is ADA Compliant?

Why WCAG Matters For Payments

With more than 2 billion disabled individuals around the world, creating an accessible experience isn’t just the right thing to do, it also means reaching a wider audience. Beyond compliance, accessible design allows consumers to do more online, including making purchases and using products.

For example, providing a secure way to validate payments inputs for blind customers can ensure that they enter the correct information. This then means that their transactions can processes correctly. Put in terms of WCAG 2.1, this means ensuring the input is perceivable by the user and that the validation option is operable for someone who cannot see.

As the world becomes ever more digital and with the continuing interest in the metaverse and other cross-platform digital content, being able to meet consumers, corporate clients, and users where they are will remain essential to business success. Providing accessible payment options does require a framework and WCAG provides a powerful starting point for better digital payments.

To learn more about how you can create exceptional accessible online payments, check out CSG Forte’s payment solutions.